If you’re in the tech/startup/growth twitterland, your timeline has gone bonkers over the past month about The Cold Start Problem by Andrew Chen. The hipster in me wants to hate it, but I’ll be damned – it’s a good friggin’ book.

The book outlines the typical company lifecycle for network-based products:

The Cold Start Problem: When you’re just getting the network off the ground.

The Tipping Point: When you hit some traction.

Escape Velocity: Woah, this thing is really taking off!

The Ceiling: Growth plateaus you hit along the way.

The Moat: Building up defensibility against competitors.

Below are my main takeaways – pieces of advice I see most founders ignore when building their network. Hope it helps!

Start Small; or, Nobody Wants to Be Alone

Ghost towns are how most networks die. Early users sign up and see the network is dead (no users, no engagement), so they leave.

The key here is to start small, with an atomic network built on meaningful connections. Get your first user, and do everything possible to have them bring their friends / colleagues / whoever-this-product-brings-value-to. In the early days, acquisition+retention+referrals are all tied together.

To illustrate this, let’s imagine you’re encountering early-Instagram for the first time. Here are two scenarios:

You sign up and have a place to interact with your friends.

You sign up and you just see a bunch of random people – not celebrities, not people from high school that you didn’t talk to… it’s just random people from across the world.

Scenario #1 is substantially better, yet most companies go with scenario #2.

While that first atomic network is being spun up, you should consider Flintstoning – creating (high-quality!) fake or internal user accounts and artificial engagement so that all of your signups have a good experience. Sounds crazy but it’s not. For more details on how Reddit, Instacart and more used Flintstoning, listen here.

Come for the Tool

This approach is a good way to get your first users, and it provides value to them regardless of the network. Instagram famously used this tactic – first starting as a simple photo filter tool with the ability to post to Facebook, before eventually launching its own networking features.

This is a good way to build up an engaged userbase, then release the network features to all of them at the same time.

Infrequent vs. Power Users

Every product can be segmented into infrequent users and power users, and the way they use your product differs drastically. As a result, you need to build a different experience for each of them. Here is how Aatif Awan described LinkedIn’s strategy to increase engagement:

“The levers you use to increase the engagement of an infrequent user are different than deepening engagement for a power user. Early users might just need a few more connections to colleagues at their company. Power users might need to discover advanced features on search, recruiting, and creating groups, so that they have new and more powerful ways to connect with people. Segmenting our users gives us the granularity to connect the right features and user education to impact their usage.”

The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs

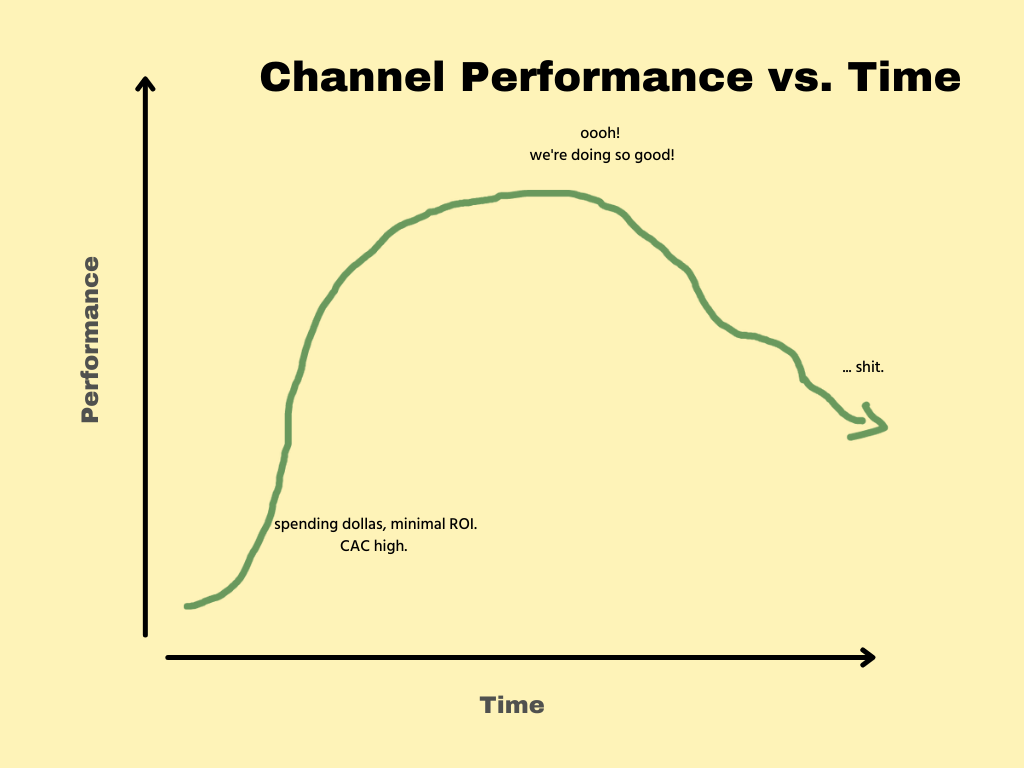

My favorite part of the book is about how marketing channel performance degrades over time. I view channel performance as the following:

Initially, it takes some time to figure out a new channel – messaging, demographic, how to get in front of your audience, aesthetic… but once you hit your stride, your marketing performance skyrockets! You’ll see CAC decrease 2-3x in just a couple months.

Eventually, however, you hit the Law of Shitty Clickthroughs – you’ve burned through your target demographic, users have learned to tune out marketing efforts, and the channel itself is actively working against you (think: how easy it was to scam people via email in the early 2000s vs. today).

To counter this, you should be doing the following:

Create organic content rather than ads

Always be looking for the next, newest marketing channel (and don’t become dependent on only a couple channels)

Instill network effects, since messages from your network (i.e. “Emily just paid you on Venmo! Sign up and cash out.”) convert at much higher rates.

Cherry Picking from Existing Networks

When Airbnb was initially getting off the ground, they went to Craigslist (where people were already listing rooms for rent) and poached them. But then, they did one better – they used Craigslist users to advertise Airbnb to others:

“Early on, Airbnb added functionality so that when a host was done setting up their listing, they could publish it to Craigslist, with photos, details, and an ‘Interested? Got a question? Contact me here’ link that drove Craigslist users back to Airbnb. These features were accomplished not by using APIs provided by Craigslist, but by reverse-engineering the platform and creating a bot to do it automatically – clever!”

If you’ve unbundled an existing product – such as Airbnb did to Craigslist – it’s best to start there as the place to build your early network.

The Rich Get Richer

When early creators start producing value, algorithms reward them. However, that means that when new creators join the network later, they face an uphill battle – which could dissuade the network from continuing to grow. To combat this, it’s important to prioritize the best content – regardless of the existing status of the user on the network.

If you reach this problem, you’ve built a substantial network for yourself and should take a second to congratulate yourself. A job well done!

Til next time,

-Zac

Wowwww Airbnb really snatched people from Craigslist like that. That's cut throat.